With the increase of private equity and external investment activity in the car wash sector, the topic of equity rollovers as a component of deal structures needs to be addressed. This article will explore what an equity rollover is, motivations behind it, and the true implications of this deal structure as it relates to sellers.

With the increase of private equity and external investment activity in the car wash sector, the topic of equity rollovers as a component of deal structures needs to be addressed. This article will explore what an equity rollover is, motivations behind it, and the true implications of this deal structure as it relates to sellers.

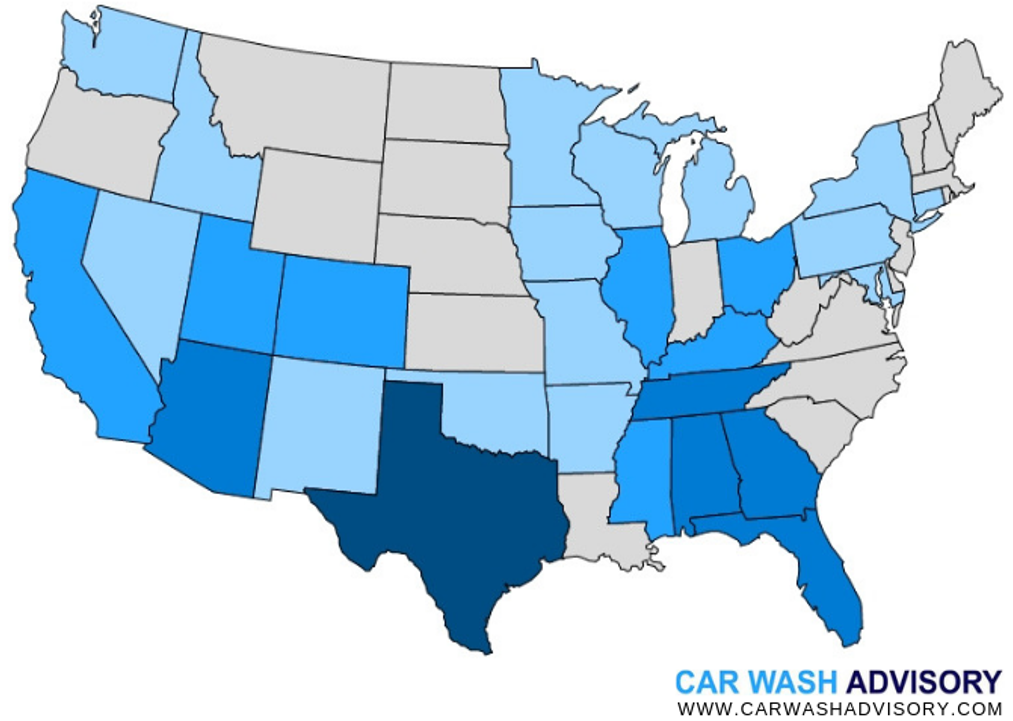

The first half of 2024 has brought a major and significant slowdown in carwash M&A, along with a stark decrease in the dispersion of acquiring parties. Transaction count is down ~46% and the number of sites sold and acquired is down nearly 40%, both compared to the first half of 2023. By way of most active acquirers, 2024 posted a large increase in deal concentration. Most notably, during the first half of 2023, the most active acquiror by transaction count was El Car Wash, having been the acquiring group in just 11% of the announced transactions. The first half of 2024 had Whistle Express representing a commanding 43% of deals as the acquiring group. In this industry report, we cover all announced M&A transactions in Q2 and provide a candid overview of market trends.

Rollover equity is a component of an acquisition deal structure. This component allows the acquiror to partially “pay” for the deal with equity of the resulting company. This allows current owners (aka the seller) to still own a piece of the business after selling it. This provides sellers the ability to still profit from the future success of the business, while also receiving significant cash today.

Although the concept of equity rollovers is relatively straightforward, their structure on an individual-deal basis is far from uniform. These transactions can be structured in a variety of ways. Variability in these deal structures typically comes in the way of equity seniority and classes offered, along with percentage ownership granted.

Let it be said that although external investment sources such as private equity funds often offer equity rollover deal structures, any acquiror can offer this type of structure. Growing industry participants, even those unconnected with external funding sources such as private equity, often do indeed offer equity rollover components in their acquisition deal structures.

Before diving into the implications to current owners and potential sellers — which we will do next month in Part II of this article — it is important to view the landscape from the opposite side: that of the acquiror. Why is the acquiror proposing this? Why are they offering this ability to rollover equity? What’s the catch?

The proposition of an acquisition with an equity-rollover component sounds too good to be true — at least initially.

At first glance, one sees a party offering to not only buy the business, not only assigning a big total “enterprise value” sticker price in terms of what it’s worth, but this buyer is also offering the seller the ability to own a piece of the company even after they sell it. Indeed, this is all true. But wait… what’s the catch? What’s in it for the buyer?

We all like to believe that humans are rationale beings. We all know that in economic studies, everything is predicated on the assumption that humans will act rationally; otherwise predicative models fail to provide value. A benefit of working with external financial bodies such as private equity groups (and growing industry participants) is that their ultimate motivations are steadfast and predictable: maximize monetary returns (or, in other words, make as much money as possible). The benefit of working with this sort of counterparty is the ability to truly understand and be comfortable with their form of “rationality” in this way.

Private equity firms and outside acquirors offer rollover equity in a transaction structure because they believe it will make them more money. It is truly that simple. And there are just two simple drivers in which this belief is predicated.

Being the more straightforward and larger of the two, acquirors believe that rollover equity structures create an alignment of interests between the current owners and the future success of the business. The idea being that if a seller still owns a portion of the business after selling it, they will do what they can to make that business a success; doing so out of the financially benefit they stand to gain from the company being worth more later down the road.

This motivational aspect of aligned incentives generally only comes into play when sellers are staying on board in some capacity post acquisition. There are exceptions to this generalization. A notable example of this is when the acquiror believes that by having the seller “on their side” — through intangible or more strategic relationship type — means the company will benefit. This is an exception nonetheless, but noteworthy given that this isn’t an enormous industry, and having strong relationships with skin in the game on one’s side certainly can help in some ways.

I have yet to find someone who enjoys paying more for anything. Private equity and industry acquirors are no exception. Offering rollover equity allows these acquirors to pay less cash out of pocket today. Private equity, and even industry acquirors, look at returns in a noteworthy yet understandable manner. These buyers care arguably as much about the total cost paid for something as they do about how much they personally have to pay out of their bank account (or in other words in “equity”).

This concept that we are now talking about is leverage. This is it. In its most basic and powerful form. And this is how buyers view their investments and returns — on a levered basis.

The primary benefit of paying less cash out of pocket for a business is simple: having more cash left in the bank account today to go do other stuff (like buy more car washes). The argument can be made that private equity and acquirors are actually paying more by offering rollover equity (at least later down the road when the expected equity value is realized). There is certainly merit to this in terms of cash being cheaper than equity in many regards depending on the circumstance. However, this isn’t a motivation as much as a cost to the acquiror.

Private equity and other acquirors can, and will, make the argument that the face value of the equity being offered is actually far higher than what it is stated as. Acquirors will present it as them doing a favor to the seller because offering this equity is effectively “costing” them more. We will touch on this more later, but again, when this is true, this is a cost and not a motivation of acquirors offering this. And let us not fall under the false belief that sophisticated financial investors (or savvy industry acquirors) are offering people more money for no other reason than kindness.

There is a secondary reason and way in which acquirors are motivated to offer rollover equity through the lens of financial engineering: the ability to boost their returns by paying less cash today. Before going further, please note that this is a nuanced point and only applies when there is a difference between the rollover equity offered and the remaining equity in the pro-forma business. This does happen, is not unheard of, and is something to be aware of. However, it does not happen on every deal.

This is when the equity offered to the seller is of a different class of security, payout preference, or proportion of post-money than that of the rest of the equity in the capital structure. What this is effectually doing is putting the seller’s rollover equity in a different bucket with different rights and payouts than the remaining equity in the business (i.e., the fund and other investors equity).

For simplicity purposes, by simply getting a 50 percent post-money proportional stake to that of the equity the seller rolled over at time of sale. Although simplified, this does effectively demonstrate how doing this can increase return metrics for the acquiror.

.jpeg)

The graphic sets out a neat and admittedly over-simplified, but nonetheless illustrative, example of this in play in a hypothetical car wash acquisition.

The graphic puts together all that has been discussed to this point. As can be seen:

Check out our Part 2 on Equity Rollovers in the Car Wash sector.

The Definitive Quick Guide: Created and Written by Car Wash Advisory Team

The key reasons using an investment bank to sell your business during economic uncertainty is a strategic decision.